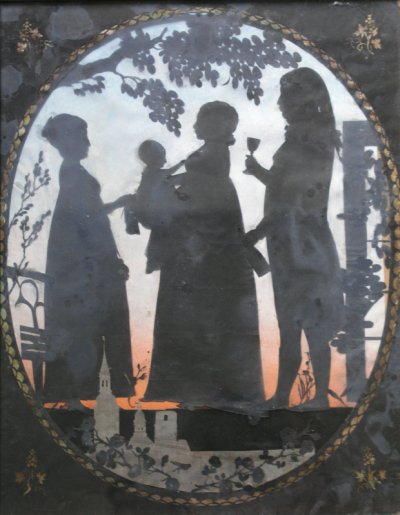

The family Sorterup in Næstved, Denmark, 1799

Franz Schmitz was the most productive silhouettist to work in the Scandinavian countries and Schleswig-Holstein in the golden age of the silhouettes. His paper cut silhouettes were so popular that literally thousands and thousands of them are still preserved today, two hundred years later.

It has been argued at all times whether silhouettes were really art. It is also true that anyone could cut a decent silhouette like any child can make a drawing. But the true artists always distinguish themselves and Schmitz had a prominent position among his professional colleagues. The elegance and ease of his portraits and his brilliant compositions were second to none. And he knew it. He named himself ”Premier-Silhouetteur” and when in good company, he would say: ”There is only one Napoleon and there is only one Silhouetteur Schmitz”.

Two things added substantially to his popularity. First, anyone could afford his silhouettes. The simplest breast portraits would cost less than a day's salary for an ordinary worker. Second, he loved to travel and he combined this desire with a well-developed commercial feeling for where to find his customers. In fact, his production was so huge and so geographically dispersed that one can almost draw his travel routes throughout Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein and along the Norwegian coastline on a map. Yet, this is only true for the years 1799 onwards. Until June 1799 when he reported as a visitor to Kiel, nothing is known about his work and travels. But he was a German, born in Bonn in 1762 and educated as a printer. When in Denmark and Norway he bragged about having worked in Germany and even in France. Yet, no single silhouette from his hand is known until the first one he made in Denmark in 1799. In fact, he was so unknown in most parts of Germany that Thieme-Becker, a major German encyclopedia of artists in 1936 described him as "Norweg. Silhouettenkünstler" (Norwegian silhouette artist). But his technique was fairly well developed in 1799 and it is hard to believe that no traces of his work in the rest of Germany should exist today. Most likely, it is just waiting to be discovered.

Silhouettes may appear to be anonymous, but they are not. The persons who were portrayed by professional silhouettists could easily recognize themselves and their family members. It is the posterity that has deemed the silhouettes anonymous, overlooking their qualities and information. But the fact is that many silhouettes were both genuine pieces of art and still contain valuable information that we can use today. In quite some cases it is possible to identify both the portrayed persons, the dating, the venue and the artist, even if little is known about a silhouette.

Most silhouettes are unsigned. They were made to order and sold to the portrayed family. Neither the artist nor the buyer seem to have had a need for a signature. But all professional silhouette artists had a number of characteristics in their portraits which can be considered their ”signatures”. Schmitz' most prominent signature was as simple as it was genious. The silhouettes were by nature flat. But imagine that you are standing in a garden in the late evening when the sun is about to set. The darker it gets, the more you will see trees and other objects as two-dimensional silhouettes like in a puppet theatre. You see the objects as two-dimensional, but you know they are three-dimensional. Schmitz uses this fact to create a trompe l'oeil for us. On his larger family portraits he uses a pastel background, blue above and orange below, illuding a sunset sky. By placing the persons, trees, fences, perhaps a corner of a house and maybe parts of a city's profile on this background, he makes us accept that the flat object we see are really in three dimensions. An inexpensive, yet impressive effect.

Other characteristics were:

- Schmitz cut by means of his scissors only, but always on a scale of appr. 1:9, meaning that portraits of grown up men would have a height of appr. 17-21 cm.

- Men were often characterized by effects in their hand illustrating their profession. Sea captains with monoculars, bakers with a bread, wine merchants with a bottle of wine etc.

- The men had a bump on top of their back.

- Women – particuarly the younger ones – had rounded breasts.

- Younger women and children had oblique, pointed and too small feet.

- Children before the age of confirmation were most often shown with toys or flowers in their hands, the oldest son with a book, younger unmarried women with some knitting.

There are certainly more characteristics to mention, but if you find several of the above mentioned in a family portrait, chances are that you are looking at a silhouette by F.L. Schmitz.

Half-length and full-length portraits can be more difficult to identify. Look for meticulous cuts in the hair, eyebrows, eyelashes, even wrinkles. On younger women look for the rounded breast and the almost suspended impression created by the oblique feet. On male portraits, Schmitz will often reveal himself in the rounded stomachs and cuts to illustrate decorations on the breast.

Was Schmitz really an artist, then? Among the art historians who have written about silhouettes, only four have covered Schmitz in some detail, the two Norwegians Einar Lexow and Henrik Grevenor, and the two Germans Christa Pieske and Ernst Schlee, both from Schleswig-Holstein. Schlee has a general reservation about silhouettes as an art. He is not sure whether to put the word "art" in citation marks or not. Lexow and Grevenor on the other hand do not hesitate to name Schmitz ”a silhouettist of European dimensions”, to which Pieske replies: "That seems to be an exaggeration". Although she acknowledges that Schmitz' half-length portraits are cut by an artistically sensitive hand, this is counterbalanced by other more crude details and the haste with which Schmitz made his silhouettes.

What the art historians tend to forget or ignore is the fact that silhouettes were not sold as art; the strongest selling point was what the great French silhouettist August Edouart termed ”Silhouette Likeliness”. The profile portraits were always the main element and the true art was in cutting an immediately recognizable portrait in a minute. The rest of the elements were ornaments of less importance. In that sense, Schmitz was a true artist despite the German art historians' reservations. One can also with Lexow argue that Schmitz' coloured backgrounds and stylistically consistent compositions are marks of a genuine artist.

But let's return to the mystery.

Where was Schmitz prior to 1799?

And where are his silhouettes of that period? His ”signatures” and compositions were so well-developed and mature in 1799 that he must have worked as a silhouettist for several years before that time. Even though we know nothing about his early whereabouts, chances are that there are many of his silhouettes out there, either as originals or as illustrations, e.g. in genealogy books, but they have yet to be identified. So how do you identify his early silhouettes?

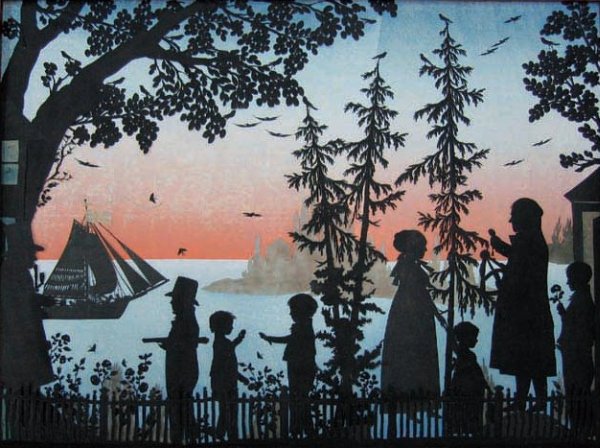

A family in Maribo, Denmark, appr. 1810-20

Photo: Anne-Marie Christensen

Although the style of the main elements, the profile portraits themselves, did not change much over time, there are noticable differences between his early and later silhouettes. Some of the changes had the purpose of creating better illusions, while others were more a question of speeding up the process of creating the silhouette. The two family portraits shown in this article illustrate some of these differences. The oldest one from 1799 is a portrait of the family Sorterup in Næstved, Denmark. As of today, this is the oldest silhouette by Schmitz that we know of. Here you see an oval inner frame (or passepartout) in blackened paper with a meticulously cut pattern around the inner edge and figures in the corners on a background of bronze gilding. A beautiful, but rather time consuming feature which is rarely seen in Schmitz' later oevre. Another feature which is seen in his very earliest silhouettes is that the background in gray – the towers of the city Næstved – is actually placed on top of the portrayed persons and not behind them. The other silhouette is said to portray a mayor's and shipowner's family of Maribo in Denmark. It has not yet been dated, but is probably from 1810-20. The oval frame has gone and has been substituted by more trees, a house, a fence, birds etc., and the background items like the ship and the island are now placed behind the portraits. The composition is now somewhat more competent. But there are also elements which have been mass produced. As an example, the three spruce in the foreground have been made using only one half-height element cut in three pieces of folded paper.

A description like the above can only be summary by nature. Therefore this promise: If you happen to know a silhouette which bears any resemblance to the descriptions in this article, I will to the best of my ability assist you in identifying the artist, the portrayed persons, the venue and the age.

Franz Schmitz' whereabouts from 1799

Whereas Schmitz' travels, routes and oevre before 1799 are completely unknown, his whereabouts from 1799 are fairly well documented. The below description focuses mainly on his visits in Schleswig-Holstein while most details of his activities in the kingdom of Denmark and the other Scandinavian countries are omitted.

10 Jun 1799 he is reported as guest in Kiel where he has spent some time already.

In the fall of 1799 he was in Denmark where he married in 1800 and the couple settled in Copenhagen from 1801. He visited Norway briefly in 1802 and on a longer trip in 1803.

17 Nov 1804 he is in Flensburg. 15 Jan 1805 he advertises in Kiel. 23 Jan 1805 he announces that he will leave Kiel five days later.

Later in 1805 he is back in Denmark. In 1807 he revisits Norway, in 1811 Sweden and from 1812 to 1814 again in Norway. Then back in Denmark from 1814 until 1817.

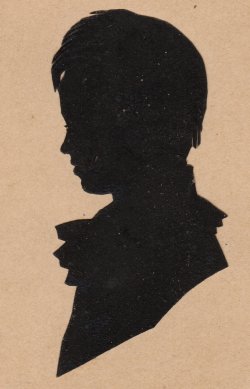

Christian Edouard Bagger (1826)

6 Sep 1817 he is in Flensburg, by the end of the year in Oldesloe. From 3 Jan until mid May 1818 he is in Lübeck. Still in 1818 he is in Bramstedt. 23 Dec 1818 he is in Schleswig and 8 May 1819 in Flensburg.

From 1819 until 1821 he was in Denmark.

From January until April 1822 he was in Lübeck again and several silhouettes from this visit still exist. He came from Schwerin and planned to continue to Ratzeburg and Hamburg, although we have yet to see evidence from these visits. He is also known to have visited Husum. The date of this visit is unknown.

From the fall of 1822 until his death in 1827 he travelled in Denmark.

Despite the obvious gaps, these travel routes are reasonably well described which is in complete contrast to the missing information about his early whereabouts.

Are the artist's travel routes important? They are because they can not only lead us to yet unidentified works of his, but they can also help us to date the silhouettes, thereby in cases providing valuable genealogy information abot the portrayed persons. In that sense, his silhouettes are a source. Perhaps not a major one, but yet a primary source.

Schmitz in museums

Believe it or not: Franz Schmitz is represented in more Danish museums than any other artist. So far, I have identified his silhouettes in more than 40 Danish museums. In Norway he is represented in more than ten museums, whereas I have so far only found silhouettes of his in few German museums, among them Schloß Gottorf in Schleswig and St. Annen-Museum in Lübeck. This apparent paradox may sound more strange than it is. Danish and Norwegian museums have a long tradition for registering their collections in common databases which are published on the Internet. Although the museums seldomly know that they own works by Schmitz, these are so easily recognizable that I have been able to identify many of his portraits this way.

Recently, the German museums seem to be adopting the same concept, so there is reason to believe that a number of Schmitz' portraits will appear in other German museums' collections in the near future.

Conclusion

The objective of the present article has been to create or renew an interest in an artist who has left a wealth of art which is not only beautiful in itself, but also offers us valuable genealogy information if properly consolidated and analyzed. There is a challenge in the general lack of knowledge about his silhouettes in Germany and in the complete gap in his whereabouts in Germany and France prior to 1800. If this article can inspire others to accept the challenge and take a closer look at the old silhouettes, my goal has been reached. And rest assured that I am willing to assist in your analysis.

Sources

In German:

"Lübecker Porträtsilhouetten um 1820 von Franz Liborius Schmitz", Dr. Christa Pieske, Der Wagen 1963, pp. 121-127.

”Schattenrisse und Silhouetteure”, Dr. Christa Pieske, Franz Schneekluth Verlag, Darmstadt 1963.

"Schleswig-holsteinische Silhouetten", Ernst Schlee, "Kunst in Schleswig-Holstein 1959", Jahrbuch des Schleswig-Holsteinischen Landesmuseums Sleswig / Schloss Gottorp, Ernst Schlee, Christian Wolff Verlag, Flensburg.

”Scherenschnitt und Schattenrisse”, Ernst Biesalski, Verlag Georg D.W. Callwey, München 1964.

”Aufzeichnungen aus der Vergangenheit des Geschlechts Schythe”, Albert Schüthe, Hamburg 1923.

In Norwegian/Danish:

"Silhouetteuren Franz Liborius Schmitz i Norge", E. Lexow, Festskriftet Kunst og Kultur, Kristiania/Oslo 1908, pp. 158-176.

”Silhouetter”, Henrik Grevenor, Norsk Folkemuseum 1922.

”Silhuetter – Skygger på væggen”, Jørgen Duus, Nyt Nordisk Forlag Arnold Busck, Copenhagen 1998.

”Konservering af et silhuetklip fra Lolland-Falsters Stiftsmuseum”, Anne-Marie Christensen, annual by Lolland-Falster Stiftsmuseum 2006, pp. 32-38.

”Silhuetter – en overset ressource i slægtsforskningen?”, Jan Tuxen, Slægt & Data, DIS-Danmark no. 3, 2002, and Slekt og Data, DIS-Norge no. 4, 2002.

"Premiersilhouetteur Schmitz i Mandal", Jan Tuxen, Slekters Gang 2013, annual by Mandal Historielag (www.mandalhistorielag.no).

"En silhuettør kommer til byen - identifikation af en samling silhuetportrætter", Jan Tuxen, By, Marsk og Geest no. 25, 2013.

Several other Danish articles, directories, parish and census records.